Walls and rocks

Drystone walls , mortared walls and limestone scar

Rocks provide the basis for particular ecosystems, both on themselves and in soil and water filled cavities. In Wensleydale, the rocks are sedimentary, belonging to the Yoredale series of alternating sandstones, limestones, coal and shale. Limestone and sandstone are most noticeable at the surface, and these two rocks provide the building materials for drystone walls and traditional buildings. Limestone, in particular, provides alkaline soils which support a characteristic flora. There is little clay in the soils, which are free draining, except on the peat covered moorland, which is much more acidic than the limestone soils at lower altitudes. Another geological characteristic is the presence of vertical veins of lead ore, or galena, below the surface. This has been the basis of a significant industry, probably from pre-history until the early 20th century. Ecologically, the result has been pollution of soils with heavy metals, particularly lead and zinc. This provided a habitat for specialist organisms that are either tolerant of, or even require, such conditions. We call them metallophytes. Metallophytes do not belong to a single biological group, but most are lichens and plants. More information is provided on the metallophytes page.

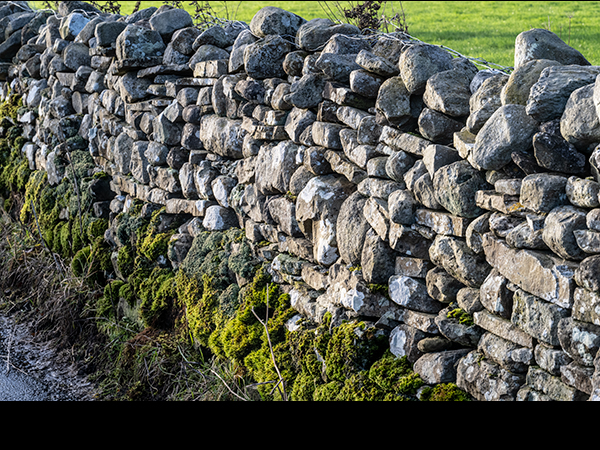

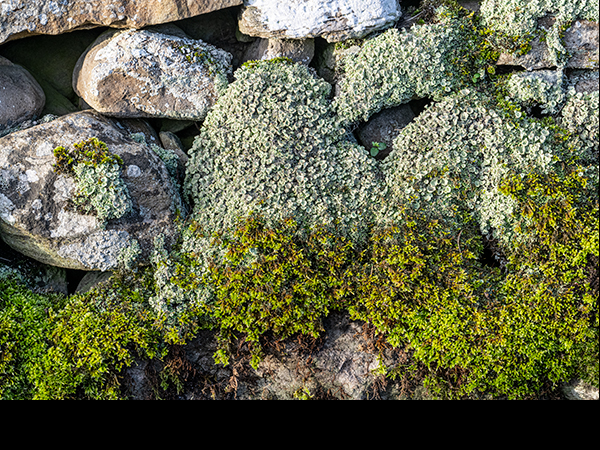

Like other parts of the Yorkshire Dales, Redmire is characterised by drystone field walls built from either limestone or sandstone, or sometimes a mix of both. Drystone walls are constructed without the aid of any bonding material such as mortar. Their strength comes from the careful interlocking of the stones. The orientation of a wall is significant and the lichen and plant cover can differ noticeably on north and south facing sides, for example. Typically, lichens, algae and cyanobacteria are the first to colonise a new wall, followed by mosses and a few ferns. Other pages deal with these groups in more detail.

The walls of buildings are mortared, and this presents a different type of habitat. Older buildings were built using lime mortar, which is relatively soft and tends to support richer lichen and plant communities than modern cement mortar. Again, the orientation of the wall is important.

Drystone walls

Slide 1: Limestone wall along Pastures Road. Limestones tend to be hard, irregular blocks, difficult to build with, dry and calcareous in nature, being composed primarily of calcium carbonate. This wall is mainly populated with the white crustose lichen Aspicilia calcarea.

Slide 2: Aspicilia calcarea, a crustose lichen which penetrates the rock and is among the first organisms to colonise this type of habitat. They can withstand prolonged drought and freezing.

Slide 3: A sandstone wall at Middle Road. The lower part is colonised by the moss Hypnum cupressiformae. This wall is east facing. Sandstones of this type are composed mainly of silicon dioxide.They are more workable and give more stability to drystone walls

Slide 4: Along with the Hypnum cupressiformae, is the trumpet shaded lichen Cladonia pyxidata.

Slide 5: A mixed lichen assembly on the deeply shaded, damp, sandstone wall at Hargill.

Slide 6: East facing mix of lime mortar, sandstone and brick, offering 3 distinct habitats occupied by different species.

Slide 7: A small piece of lime mortar from the previous wall, showing cyanobacteria (black) and the lichens Candelariella aurella (orange), and Leprocaulon calcicola (white).

Limestone scar

Redmire Scar is a long, low outcrop of limestone in the northern part of the parish and effectively separates the moorland from the farmland. The illustration here shows a small waterfall, where Barney Beck crosses the scar, and detail of Maidenhair Spleenwort (Asplenium trichomanes), a small fern. The whiteness of the limestone is increased by a covering of the lichen Aspicilia calcarea. The scar also provides a habitat for Ash (Fraxinus excelsior) in the cracks and Ivy (Hedera helix), both visible to the right of the waterfall.

The pasture above and below the scar is of a type called calaminarian grassland, a rare habitat associated with historic lead mining sites, such as the nearby Cobscar Rake. Calaminarian grassland supports a distinctive flora.